For many of my friends in the northeastern United States, the spring of 2015 is starting off with a nasty dry spell.

Even in a non-drought year, water often goes lacking on vegetable farms because of a lack of infrastructure, poor practices, insufficient monitoring, and a simple failure to get out there and put the water on that your crops need.

In 2012, during the extreme drought that we experienced in the Midwest, I had the opportunity to work with and visit several farms, as well as to drag my own farm through the dust. It was a great year to learn about what to do, and what not to do, when it comes to managing irrigation on your crops.

Use a Pressure Gauge – Running an irrigation system without a pressure gauge is like driving a tractor without a tachometer. Nozzles and drip emitters are designed to work at specific pressures (drip emitters are generally designed to work best at 8 – 12 psi), and you can’t judge those pressures by eye or by feel.

You want to check pressure at the beginning of your distribution lines. For drip irrigation systems and other low-pressure systems, I like the pressure gauges that are mounted on a stake, with a barbed poly connector to tie into the header line.

Monitor Soil Moisture – Nobody has spoken to me more strongly about the potential for irrigation management to maximize yields than Jim Crawford of Pennsylvania’s New Morning Farm. Jim monitors soil moisture using a standard soil probe, and the “Look and Feel” method for analysis. A soil probe like the JMC Soil Sampler with Footstep from Gempler’s lets you take a core sample twelve inches deep without too much bending; you can buy cheaper ones, but this is a nice option for making water sampling easy.

Most guides to monitoring irrigation with the “Look and Feel” method for monitoring soil moisture just duplicate information. Louisiana State University has a guide, Irrigation Scheduling Made Easy, with a better-than-average presentation of the concept and practical applications.

Keep in mind that most vegetables have fairly shallow root systems, generally from 6 – 18 inches. If you aren’t keep that area of the soil profile supplied with adequate water, you’re hampering your crop’s ability to perform.

Size Your Supply Lines – Irrigation systems, no matter how small, have supply lines, header lines and distribution lines. The supply lines get water to the field, header lines get the water to the distribution lines, and the distribution lines put the water in the field. These supply lines should be bigger (or at least not smaller) than the header lines, and the header line should be bigger (or at least not smaller) than the distribution lines.

Too many farms that I visited had supply lines that were just too small, reducing pressure and restricting the flow of water, which reduces the efficiency of water distribution. Beginning farmers especially were relying on garden hoses, the most expensive and least effective option for supply lines.

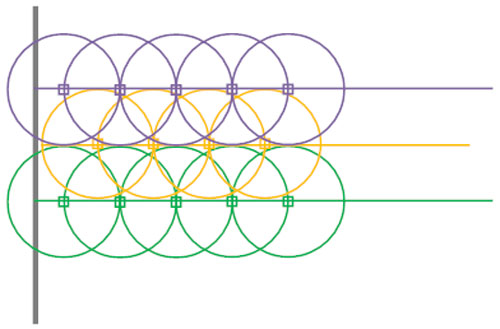

Set up Overhead Irrigation Systems Correctly – For most irrigation systems, lay out sprinkler heads such that the arc of each sprinkler just about reaches the next riser, and so that the sprinklers are offset from each other in adjacent lines. This ensures full, even coverage.

Even in a non-drought year, water often goes lacking on vegetable farms because of a lack of infrastructure, poor practices, insufficient monitoring, and a simple failure to get out there and put the water on that your crops need.

In 2012, during the extreme drought that we experienced in the Midwest, I had the opportunity to work with and visit several farms, as well as to drag my own farm through the dust. It was a great year to learn about what to do, and what not to do, when it comes to managing irrigation on your crops.

Use a Pressure Gauge – Running an irrigation system without a pressure gauge is like driving a tractor without a tachometer. Nozzles and drip emitters are designed to work at specific pressures (drip emitters are generally designed to work best at 8 – 12 psi), and you can’t judge those pressures by eye or by feel.

You want to check pressure at the beginning of your distribution lines. For drip irrigation systems and other low-pressure systems, I like the pressure gauges that are mounted on a stake, with a barbed poly connector to tie into the header line.

Monitor Soil Moisture – Nobody has spoken to me more strongly about the potential for irrigation management to maximize yields than Jim Crawford of Pennsylvania’s New Morning Farm. Jim monitors soil moisture using a standard soil probe, and the “Look and Feel” method for analysis. A soil probe like the JMC Soil Sampler with Footstep from Gempler’s lets you take a core sample twelve inches deep without too much bending; you can buy cheaper ones, but this is a nice option for making water sampling easy.

Most guides to monitoring irrigation with the “Look and Feel” method for monitoring soil moisture just duplicate information. Louisiana State University has a guide, Irrigation Scheduling Made Easy, with a better-than-average presentation of the concept and practical applications.

Keep in mind that most vegetables have fairly shallow root systems, generally from 6 – 18 inches. If you aren’t keep that area of the soil profile supplied with adequate water, you’re hampering your crop’s ability to perform.

Size Your Supply Lines – Irrigation systems, no matter how small, have supply lines, header lines and distribution lines. The supply lines get water to the field, header lines get the water to the distribution lines, and the distribution lines put the water in the field. These supply lines should be bigger (or at least not smaller) than the header lines, and the header line should be bigger (or at least not smaller) than the distribution lines.

Too many farms that I visited had supply lines that were just too small, reducing pressure and restricting the flow of water, which reduces the efficiency of water distribution. Beginning farmers especially were relying on garden hoses, the most expensive and least effective option for supply lines.

Set up Overhead Irrigation Systems Correctly – For most irrigation systems, lay out sprinkler heads such that the arc of each sprinkler just about reaches the next riser, and so that the sprinklers are offset from each other in adjacent lines. This ensures full, even coverage.

Monitor Your System – You can’t just turn your system on and walk away. When you turn the irrigation system on, you need to check to make certain everything is operating correctly. Is the drip tape leaking? Are the sprinklers all rotating?

Water at Critical Growth Stages – If you have to triage your water supply, focus the water where it will provide the most benefit. Germinating succession crops is obviously critical if you want to keep a supply of vegetables in the pipeline. Pay special attention to water supplies during tuber initiation for potatoes; fruit set and sizing and tomatoes, zucchini, and other fruiting crops; and head sizing in crops like broccoli and cauliflower.

One farm I worked with during the drought had a massive crop of tomatoes that was essentially dry-farmed all summer long. Just as harvest was getting under way, they got the first drenching rain in months – and cracked every tomato on the vine, resulting in massive crop losses.

If You’re Not in a Drought – If you’re in the vegetable business for long, you will experience a drought sooner or later. In 2012, the farms – beginning and experienced – who had invested in adequate and practical watering systems had their most profitable year ever. Irrigation is one area of the farm where, when you need the capacity, you just can’t get by without it. And there is no reasonable work-around. I’ve watched vegetable farmers haul water in 1,500-gallon tanks during a drought, and it’s a money-losing proposition. Invest now. Not only will the investment pay off in a drought year, but an easy, efficient irrigation system pays off in increased yields every year that you use it wisely.

Water at Critical Growth Stages – If you have to triage your water supply, focus the water where it will provide the most benefit. Germinating succession crops is obviously critical if you want to keep a supply of vegetables in the pipeline. Pay special attention to water supplies during tuber initiation for potatoes; fruit set and sizing and tomatoes, zucchini, and other fruiting crops; and head sizing in crops like broccoli and cauliflower.

One farm I worked with during the drought had a massive crop of tomatoes that was essentially dry-farmed all summer long. Just as harvest was getting under way, they got the first drenching rain in months – and cracked every tomato on the vine, resulting in massive crop losses.

If You’re Not in a Drought – If you’re in the vegetable business for long, you will experience a drought sooner or later. In 2012, the farms – beginning and experienced – who had invested in adequate and practical watering systems had their most profitable year ever. Irrigation is one area of the farm where, when you need the capacity, you just can’t get by without it. And there is no reasonable work-around. I’ve watched vegetable farmers haul water in 1,500-gallon tanks during a drought, and it’s a money-losing proposition. Invest now. Not only will the investment pay off in a drought year, but an easy, efficient irrigation system pays off in increased yields every year that you use it wisely.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed