When a company buys your product to sell it to somebody else, they charge more to their customers than they pay you - that's how they cover their own expenses, and how they make money in return for their management expertise, risk, and investment.

The additional amount they charge can be expressed in two different ways: as a markup, or as a margin. A markup describes the additional percentage a reseller makes on the product, whereas a margin describes the percentage of the selling price that a reseller makes over and above the price they paid for it.

Understanding margins can help you estimate the price a store or wholesale distributor is paying for their product. Margins are also part of the language of the trade, so understanding margins puts you on a more professional footing when you talk with buyers.

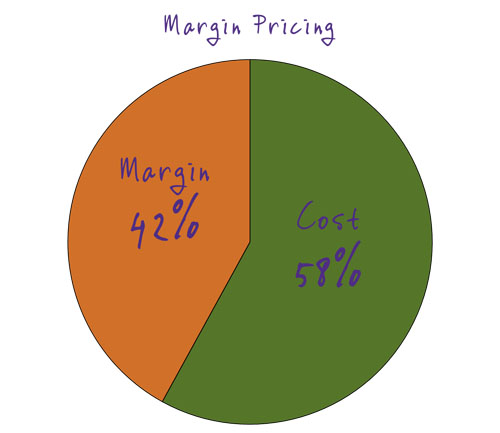

Margins are useful because they describe the "gross profit margin" that a reseller actually gets. The margin has to cover all of the reseller’s expenses related to selling produce. For example, natural food stores in my area use a 42% margin as their basis for calculating retail produce prices. That 42% of their selling cost has to cover all of the store's direct expenses related to selling produce: the labor, bags, and display items, as well as the overhead costs of running the store: electricity, rent, bookkeeping, cash registers, and everything else.

The additional amount they charge can be expressed in two different ways: as a markup, or as a margin. A markup describes the additional percentage a reseller makes on the product, whereas a margin describes the percentage of the selling price that a reseller makes over and above the price they paid for it.

Understanding margins can help you estimate the price a store or wholesale distributor is paying for their product. Margins are also part of the language of the trade, so understanding margins puts you on a more professional footing when you talk with buyers.

Margins are useful because they describe the "gross profit margin" that a reseller actually gets. The margin has to cover all of the reseller’s expenses related to selling produce. For example, natural food stores in my area use a 42% margin as their basis for calculating retail produce prices. That 42% of their selling cost has to cover all of the store's direct expenses related to selling produce: the labor, bags, and display items, as well as the overhead costs of running the store: electricity, rent, bookkeeping, cash registers, and everything else.

In other words, if the store is charging $1.00 for a bunch of parsley, they’ve got $0.42 to cover all of the costs of selling that parsley, because they spent $0.58 to purchase it for sale in their store.

And, even though they use a 42% margin to calculate their prices, they expect to realize only a 35% margin on their produce sales overall, since they lose a certain amount to "shrink," due to spoilage, trimming, blemishes, customer handling, and so forth.

Different outlets have different cost structures, so they use different margins.

A wholesale distributor I've worked with uses a standard margin of 23%. They have lower expenses per unit sold than a retail store does, so they don't need to charge as high of a margin.

In fact, different product lines in a grocery store also have different cost structures, so the margin on canned goods is going to be different than it is on fresh produce, since canned goods don't have the same risk of spoilage and don't have the same labor requirements as fresh produce.

And that's where margins matter to market farmers. When you have higher selling costs, you need a higher margin. When you sell produce at farmers market, your costs - labor, stall fees, shrink - are higher than your cost to sell to a retail store. If you sell at a retail store and at a farmers market, your prices in each of those markets should reflect your costs in each of those markets. It costs the same amount of money to grow a bunch of kale for your farmers market stand as it does to grow a bunch of kale for a retail store, but it costs a lot more to sell that bunch of kale at a farmers market.

We'll continue this topic next week when we get into margin math, so stay tuned!

And, even though they use a 42% margin to calculate their prices, they expect to realize only a 35% margin on their produce sales overall, since they lose a certain amount to "shrink," due to spoilage, trimming, blemishes, customer handling, and so forth.

Different outlets have different cost structures, so they use different margins.

A wholesale distributor I've worked with uses a standard margin of 23%. They have lower expenses per unit sold than a retail store does, so they don't need to charge as high of a margin.

In fact, different product lines in a grocery store also have different cost structures, so the margin on canned goods is going to be different than it is on fresh produce, since canned goods don't have the same risk of spoilage and don't have the same labor requirements as fresh produce.

And that's where margins matter to market farmers. When you have higher selling costs, you need a higher margin. When you sell produce at farmers market, your costs - labor, stall fees, shrink - are higher than your cost to sell to a retail store. If you sell at a retail store and at a farmers market, your prices in each of those markets should reflect your costs in each of those markets. It costs the same amount of money to grow a bunch of kale for your farmers market stand as it does to grow a bunch of kale for a retail store, but it costs a lot more to sell that bunch of kale at a farmers market.

We'll continue this topic next week when we get into margin math, so stay tuned!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed