The checkbook doesn’t stretch enough to pay the bills.

If you can’t pay your bills and ongoing expenses, you’ve got trouble. This includes living expenses as well as ongoing farm expenses. And while it seems obvious, it’s easy to ignore and think that things are going to get better on their own.

Carrying open accounts past 60 days.

Carrying open accounts with vendors can be a smart way to manage cash flow, but if you have to stretch your payables too far, that’s a sign that something’s wrong with your cash flow. Carrying open accounts for too long can make you an undesirable customer to important input suppliers, setting you up for future problems.

Forgoing necessary inputs.

This seems like a no-brainer, but too many farmers skimp on feed, water, fertilizer, and other necessary inputs because they don’t have the cash to pay for them. As a result, crops and livestock don’t perform as well as they should, so income goes down, and then, next year, you’ve got even less money to pay for the necessary inputs. And the cycle repeats itself, getting a little worse each time.

Selling inventories.

To create short-term cash, you might be tempted to sell input inventories that you will have to replace later. The same thing is true when it comes to selling CSA shares in the fall to generate fall cash-flow - you’ll likely find yourself in the same situation next year unless you make some changes to your operation. This is almost always a losing proposition.

Accepting lower-than-market prices.

If you have to sell your products at lower-than-market prices to generate short-term cash, that’s a sign that things aren’t going well. You should be selling products to make money, not just to plug cash-flow holes.

Avoiding the Wreck

If you identify hazards early enough, you can take actions to avoid them. But it’s important to act fast.

Talk to your lender immediately.

No, really, don’t wait! Most borrowers hide financial problems from their lenders until it’s too late, but hiding problems from partners – whether they’re business partners or personal partners – is never a good idea. Remember, in most cases, the bank simply does not want your farm – they will work with you to figure out how to avoid having a bad loan on their books. And it’s easier to make adjustments when the crisis point is further away, rather than waiting until you’ve washed up on the rocks.

Change the amortization on your loans.

Cash flow isn’t everything, but it is an important thing. Changing the term of a loan can be a win-win for you and the bank, since they don’t end up with a bad loan on their books and you can reduce your monthly payments. And, of course, if things get better, you can always increase your payments back to their original level.

Consider a line of credit.

A short-term infusion of cash with a payback plan is usually a much better option than having a dozen vendors banging on your door and ringing your phone wondering when they are going to get paid.

Increase Success

This is perhaps the most important way to avoid a wreck!

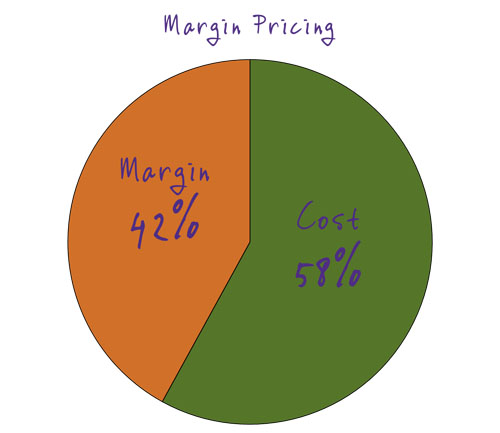

In agriculture, profitability has three components: scale, costs, and utilization.

You need to produce enough product to cover your overhead expenses. It costs the same amount of money and time to have a website or write a newsletter whether you sell $1,000 worth of carrots a week or $50,000. And many variable costs have a certain baseline to them - trucking and handling charges are often based on the pallet or the truckload, regardless of how much product is on the pallet or in the truck. The number of pallets is a variable cost, but each pallet costs the same whether it's carrying $300 or $3,000 worth of product.

You need to drive down your cash expenses as much as possible. Don't skimp on the water and fertilizer that make your crops grow, but don't pay more for them than you have to - unless paying more for them provides value in another way. (I try to buy my tools locally, and pay more for them than I would at the big box store, because my local hardware store provides tons of help and advice with smaller purchases; I buy seeds from a high-quality vendor rather than getting the sweepings from the seed room floor from a cheaper source.)

You need to maximize utilization of your assets - all of your assets. If you are in the crop production business, every acre needs to be working for you, whether it's growing a cash crop or next year's fertility. If you have employees, you need to maximize their productivity. If you are selling meat, you need to maximize your use of the entire carcass, getting the best price on every part of the animal. In the delivery business, your trucks need to run as many days a week as possible, and as full as possible whenever they are running.

Most often, the changes that growers need to make in order to avoid a wreck come from improved management, rather than significant investments. Focus on investments that increase your ability to monitor the critical elements of your operation – most of these can be had at very little cost.

Don’t Wait for the Warning Signs

Of course, if everything in your operation is going great, you probably won’t have anything to worry about. But just like your car can seem to be running just fine right up until your tire blows out, farm financial troubles have a way of sneaking up on you. The best way to avoid a financial wreck is to look out far in advance. And the best way to do that is to institute a regular pattern of financial planning and monitoring.

- Weekly - Are there bills to pay? Do I have money in my bank account? What’s my credit card balance?

- Monthly - Are there any outstanding receivables? Does the bank think I have as much money as I think I have? How is my financial plan working out?

- Quarterly - What do I owe the government for payroll and other applicable taxes?

- Yearly - What do I owe the government now? How have my assets, liabilities, and equity changed in the last year? Did I make progress last year?

Every year, farm businesses should complete a balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows, and evaluate the resulting financial ratios. These reports provide invaluable feedback on business progress from year to year, as well as predicting issues that are coming down the pike.

In addition, creating an ongoing financial history of your farm with these statements will not only demonstrate business growth, it will also demonstrate to a lender/investor that you take your business seriously; one of the primary complaints I have heard from lenders is that they are being asked to finance lifestyle choices under the guise of a business investment.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed