Fixing the sheep fence is urgent when the sheep are eating your beets.

Changing the oil and performing other maintenance on the tractor is important.

Fixing a broken tractor becomes urgent when rainclouds are on and the crew is ready to go out to the field for transplanting.

Spending focused time with your kids is important.

Dealing with a meltdown is urgent.

Getting the flame weeder set up and ready to clean the weeds off of the carrot field the day before the carrots germinate is important.

Flaming on the right day is urgent.

Eating well is important.

Being hangry is just ugly.

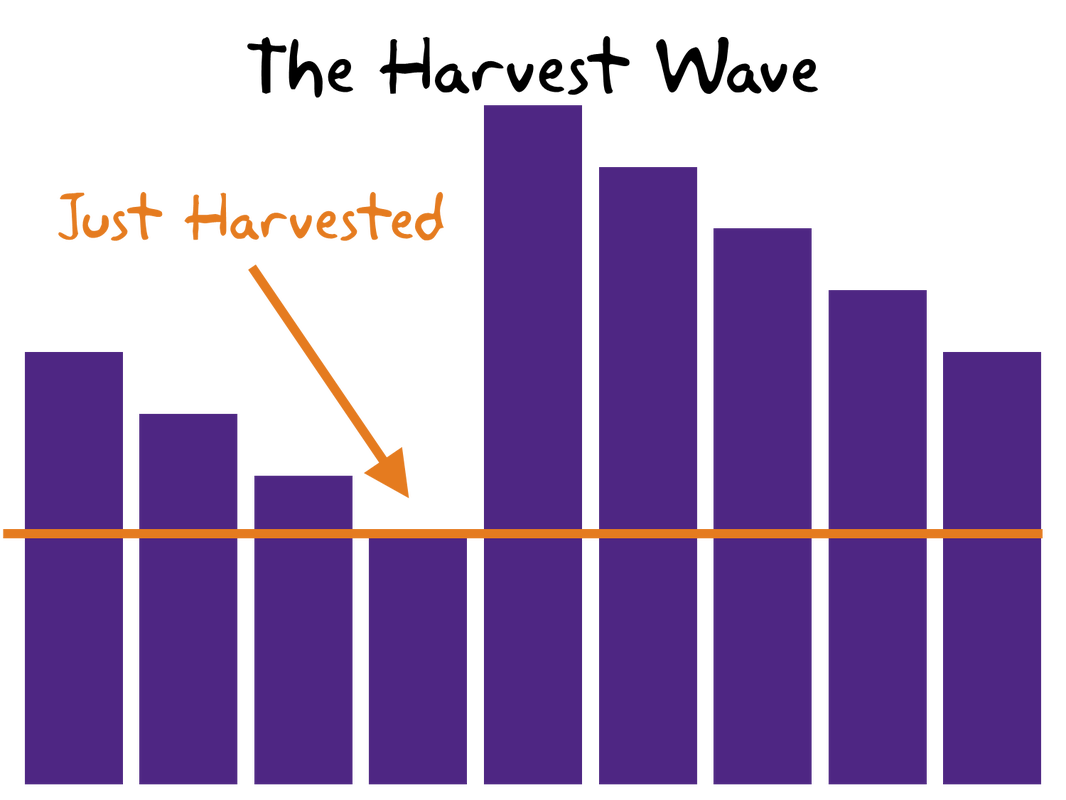

Importance tends to bleed over into urgency as time passes. And it tends to ramp up the work and the stress level and the expense. Not fixing the fence before the sheep get out means that you not only have to fix the fence, you have to put the sheep back in.

Plus, you’ve fed the sheep on relatively expensive beets. Just be glad they didn’t find the radicchio.

When you take care of the important things, the urgent things don’t show up as often. And it almost always takes less time. Taking two extra minutes to make sure the fence is hot and tight means that you don’t have to chase the sheep.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed