This seemed like the best way to maximize our yields, but in the end, it really just maximized our work as we spent as much time walking and evaluating each plant as we did harvesting. It also resulted in a field that had a patchwork quilt of regrowth size and quality. A chard plant with eight nice leaves would sit right next to one that had been harvested down to its nubs, or a thyme plant would be half-harvested while the other half was going to flower. And pretty soon, some plants were overgrown and woody, while the remaining plants were over-harvested to meet demand.

At the time, we were rotationally grazing sheep, and I had been reading about proper management of pastures in rotational grazing - basically, you keep the sheep (or whatever other ruminants you're grazing) on a given piece of pasture until it has all been eaten down to the best level for managing the target species in that paddock, then move the herd to new section of pasture; and you manage the grazing to prevent the plants from switching from green vegetative growth to reproductive, flowering growth.

I realized that we could apply some of the same principles to growing and harvesting our herbs and vegetables:

- Harvest everything in a section of the bed to the same level;

- Create a “wedge” of growth;

- Manage plants for vegetative, not reproductive, growth; and

- Manage our “grazing” to match the variable growth rates throughout the year.

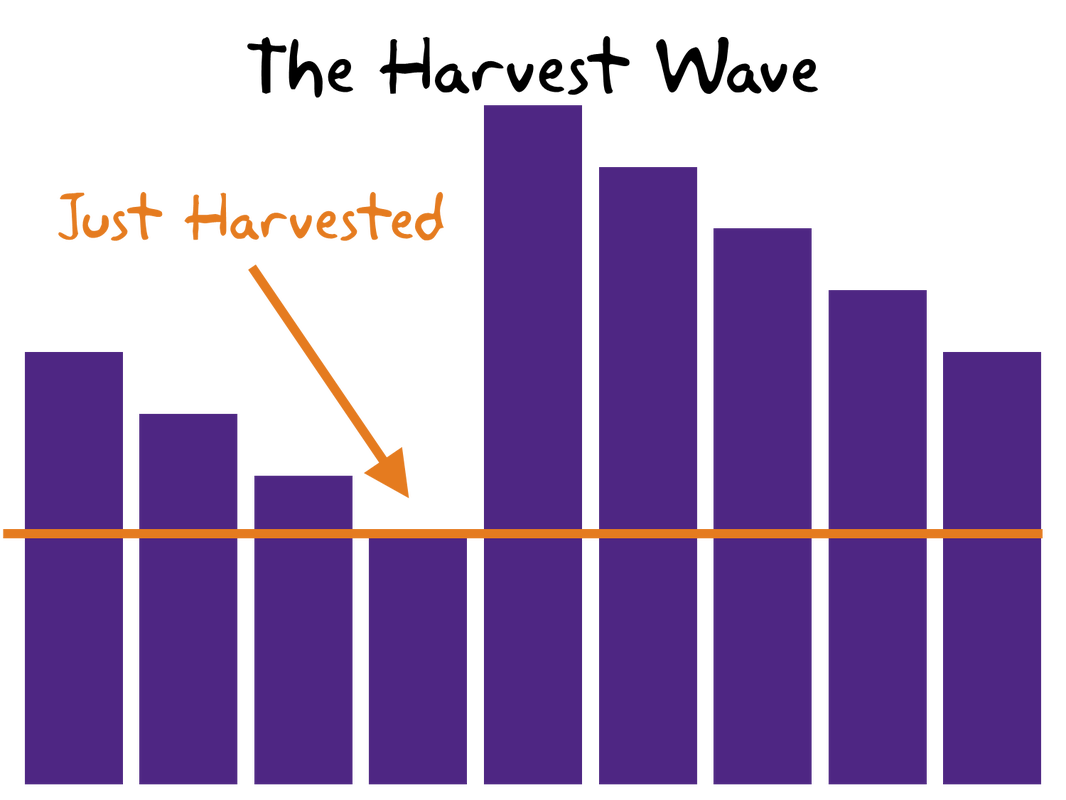

Harvest started at one end of the bed, and moved steadily down the bed with each harvest. The result was a stepped appearance, as illustrated in the picture.

Surfing the harvest wave allowed us to minimize harvest labor by reducing the number of steps taken because it encouraged even regrowth and discouraged workers from hunting-and-pecking their way through the field. It also maximized yields by helping us identify when a section of the bed needed maintenance to stay green, healthy, and growing.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed