- A complaint is just a project waiting for definition;

- Always ask yourself, “What’s my end game?”’ and

- All I can do is all I can do.

These are three hard lessons to learn, and even harder lessons to accept. Trust me. I speak from experience.

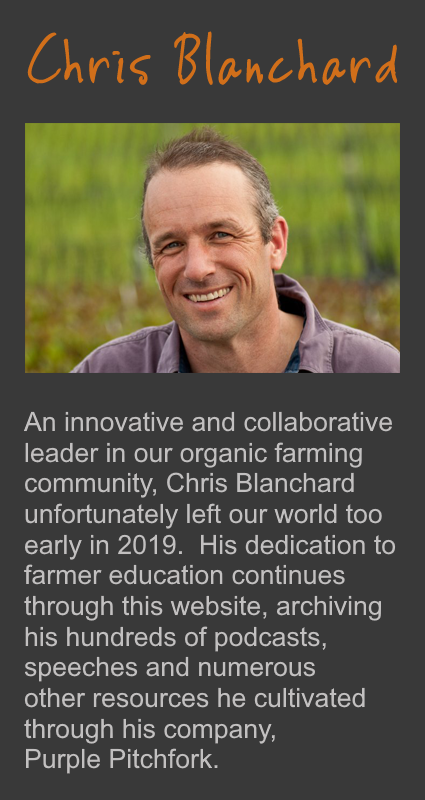

Given some developments in the non-Purple Pitchfork areas of my life, I’m taking a hard look at these lessons, and I’m making some adjustments to Purple Pitchfork, at least for the time being.

I’m going to take a break from writing essays for this weekly newsletter. As much as I enjoy doing the work, and as much as I’ve heard that you value it, it’s more than I can do right now. I expect that I’ll still kick out the occasional essay, perhaps with some longer pieces, and maybe things will change again in a way that allows me to resume the weekly rhythm of writing.

We’ll still be in touch with podcast information. And I’m still planning to get a podcast out every Thursday, too.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed