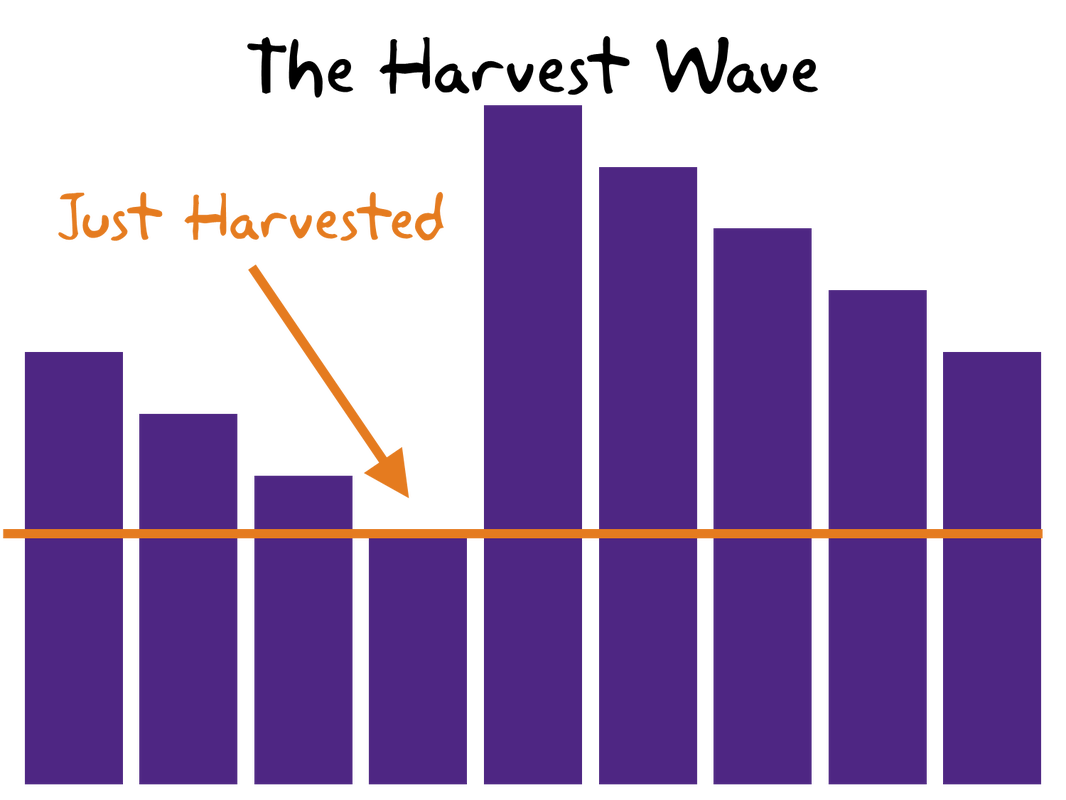

But that lower interest rate comes at a cost – it increases the borrower’s risk. Short-term loans have higher minimum payments, and require you to service the debt regardless of what else happens in your business.

Cash is king, and it pays to stay flexible. You never know what crises or opportunities might come your way to change the availability of cash in your operation.

You can always pay off a loan early, but it’s much harder to extend it once you’ve signed the loan documents.

(By the way, it’s never advisable to use an annual crop note [a cash flow loan] to finance capital purchases. Borrowing on a long-term note and paying it off the same year is a much more prudent course of action.)

RSS Feed

RSS Feed